Deep Tech Startups & Venture Capital: An Analysis of 2025 | Chapter 4

The annual report on the Deep Tech Cycle — 2025 in Themes: where value pools across mobility, space, defense, biomanufacturing, robotics, and much more.

Deep tech spent 2025 proving that “industrial” is no longer a metaphor.

It showed up in trucks and ports, launch pads and lunar landers, reactors and robots, fermenters and hospital corridors. What used to look like separate verticals—mobility, space, defense, food, health, automation—behaved as a single cycle of infrastructure, regulation, and cash flows.

As you know, we believe that a sharper view of what’s ahead begins with a disciplined reading of what already happened. That’s why, at the start of every year, we go back through the prior twelve months—facts, data, capital flows, policy moves, and weak signals—and reconstruct the tape in detail.

This is always useful, but it is essential in deep tech: unlike more mature, standardized sectors like SaaS, there are still no stable benchmarks, no widely accepted valuation playbooks, and very few clean comparables. Deep tech cuts across multiple technologies and multiple industries at once; if you only look at one slice, you miss the cycle.

In practice, deep tech is best understood as a category of companies, talent, and enabling infrastructure that underwrites industrial development through high-intensity technology: new compute and materials, new machines and processes, new biology and energy systems.

And if we allow ourselves a slightly romantic lens, we might say that deep tech startups turn hard science into hard power—shaping the future not just in code and screens, but in ports, grids, fabs, fields, and clinics, and unlocking capabilities that will define the next industrial age.

This annual report is organized in four chapters, and this is the fourth and final one.

In Chapters 1 and 2, we followed 2025 “in data,” month by month—building a factual ledger of fundraises and down-rounds, facilities announced and delayed, policy decisions that unlocked projects and those that stalled them.

In the second half, we shifted to a sectoral perspective and mapped where value began to pool across the stack of verticals—how quantum, materials, semiconductors, biomanufacturing, robotics, energy, and more started to behave as interconnected layers of the same industrial system.

More specifically, in Chapter 3 we replayed 2025 through the lens of compute, interconnects, and materials—following semiconductors and photonics, advanced materials and industrial chemistry, quantum technologies, AI infrastructure and data centers, energy and storage, machinery and manufacturing, critical minerals, carbon management, the built environment, and nuclear—to see where bottlenecks and control points emerged in the stack.

This Chapter 4 completes the picture.

Here, we revisit 2025 through seven applied systems: mobility and transportation, space and aerospace, defense and cybersecurity, biomanufacturing and synthetic biology, agri- and food-tech, biotechnology and therapeutics, and robotics and autonomous systems. Instead of asking only “what was invented,” we ask how those inventions behaved when they met factories and fleets, regulators and hospital workflows, procurement teams and mission operators.

Across the chapter, a few questions keep repeating:

When does a “product” become infrastructure—part of a corridor, constellation, bioreactor fleet, or hospital pathway—rather than a standalone gadget or SKU?

Where does value concentrate when data, uptime, safety, and compliance matter as much as hardware specs or wet-lab performance?

How do states, corporates, and capital providers share roles as regulators, buyers, offtakers, and financiers in dual-use and mission-critical systems?

And for founders and investors, what does it mean to build and back companies whose destiny is to live inside industrial and policy cycles measured in gigawatts, tonnes, sorties, or bed-days—not only in MAUs or ARR?

What follows is 2025 seen through those operating systems.

From corridors in the sky and at sea to reactors, fermenters, fields, and factory lines, we trace how deep tech became embedded in the everyday machinery of the economy—and what that implies for the next phase of the cycle.

Enjoy the read!

– The Scenarionist Team

1. Mobility & Transportation Systems

In 2025, mobility and transportation revolved around a simple question: who controls the infrastructure and data rails that actually keep people and goods moving.

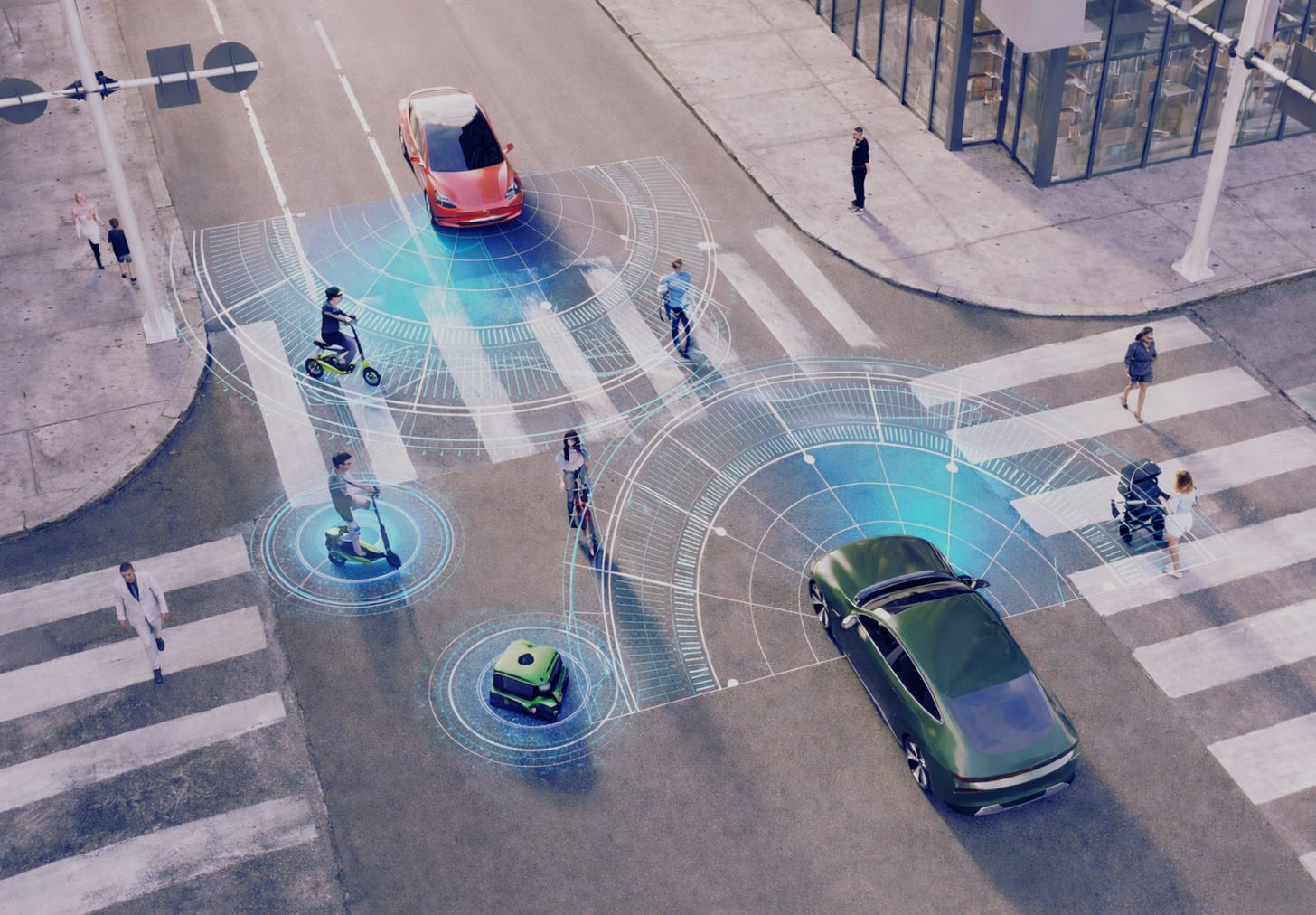

Autonomy appeared as an operational layer inside freight networks, last-mile delivery, and new forms of regional aviation and air cargo. EVs took on a dual role as vehicles and as grid-edge assets, with bidirectional charging and virtual power plant use cases integrating them into the power system.

Ports and shipping firms treated fuels, data, and compliance as a single system, where digital tracking and emissions reporting plugged directly into everyday logistics. Regulators also progressed on advanced air mobility, turning concepts into early rulebooks.

Across these domains, a set of background questions kept resurfacing.

When does a robot, truck, or aircraft function as part of an industrial system rather than as a standalone gadget?

Where does value accumulate when routing, charging, and risk data matter as much as the hardware that moves people and goods?

And for founders and backers, what it means to scale mobility companies that sit on the boundary between transport, energy, and national regulation, in markets where software, infrastructure, and compliance work as a single stack.

1.1 Autonomy after the shake-out: freight, last-mile, and real unit economics

The most concrete uses of autonomy appeared along repeatable routes where cost discipline and uptime decide outcomes. Corridor-based deployments from players like Waabi and Kodiak illustrate this pattern: high-utilization trucks operating on a limited set of lanes under tight contracts, with simulation-heavy stacks and deep integration with shippers and OEMs.

At the small-vehicle end of the spectrum, Robomart’s RM5 offered a detailed and measurable thesis for last-mile delivery.

The system uses a shuttle-sized Level-4 electric van carrying ten climate-controlled lockers of around 50 pounds each. Total payload sits near 500 pounds, with a top speed of 25 mph and a range of roughly 112 miles. The business model mirrors an Instacart-style marketplace inside the company’s own app, paired with a flat 3 dollar delivery fee that features no markups, no service fees, and no tips. Public statements claim up to 70% lower fulfillment costs versus human couriers.

The framing is instructive. In this model, autonomy turns a van into a rolling shared micro-warehouse. The economics live inside batch routing, locker utilization, and customer acquisition costs. The robot is a node in a logistics network, and the brand lives in the marketplace and service promise rather than in the chassis.

In long-haul trucking, the sector entered a second act.

A wave of shutdowns, down-rounds, and pivots cleared the field, leaving a smaller set of companies pursuing narrower, more structured opportunities.

The remaining leaders, including Waabi and Kodiak, focused on specific corridors, strong relationships with shippers and truck makers, and stacks built around large-scale simulation. The Kodiak SPAC listing reflects this view: autonomous trucks on a defined set of lanes, under tight contracts, with performance and cash flows that investors can benchmark like infrastructure rather than like open-ended research.

Autonomy in aviation followed a similar industrial tone. Reliable Robotics secured a $17.4 million U.S. Air Force contract to retrofit a Cessna 208B Caravan with its autonomy stack. The agreement runs into 2026–27 and includes uncrewed cargo missions within regular operations, not only test flights. The objective is a standards-based path to certifiable, aircraft-agnostic autonomy that slots into existing airspace rules and logistics chains.

The system automates taxi, takeoff, en-route flight, and landing, with multilayer redundancy and advanced navigation. It keeps the autopilot engaged across all phases of flight. The FAA has accepted certification plans and system requirements for the navigation and continuous-autopilot system as part of the path to a supplemental type certificate. The Caravan platform becomes a test case for integrating uncrewed cargo aircraft into everyday airspace and logistics networks.

For builders and backers, this picture sets clear expectations. Autonomy creates value when it runs on corridors, lanes, and air routes that already support contracts, utilization targets, and measurable operating margins.

1.2 EVs, fleets, and the grid edge: vehicles as energy assets

Electrification revolved around orchestration. The main question was how to coordinate electrons across fleets, chargers, and buildings and how to turn vehicles into stable assets at the edge of the grid.

On the software side, Volteras presented itself as a “Stripe for electrons”. The company built an API-first energy and vehicle-data platform that lets automakers, fleets, and partners treat charging information as a programmable service rather than as a patchwork of proprietary apps and RFID cards.

The platform sits between automaker apps, fleet management tools, and public charging networks. It normalizes real-time data from vehicles and energy assets so that session details, status, and pricing feed into consistent customer experiences and billing flows.

On other hands, Energy Island Power explored vehicle-to-home as a resilience tool. Its compact bidirectional kit uses capable EVs to feed a few kilowatts into critical loads such as refrigerators, lights, and routers, with round-trip efficiency around 80% in lab tests. The hardware is plug-and-play, requires minimal electrical work, and focuses on selected circuits instead of full-home backup. This design turns the car into a simple backup device for outages and extreme weather, and it creates a clear product story for insurers, utilities, and homeowners.

In markets with unreliable grids or frequent climate shocks, these architectures reposition EVs as flexible, distributed storage assets. Vehicles no longer act only as loads; they support backup power, grid services, and new financing structures where energy revenue streams contribute to the economics of the car.

Upstream, cell supply started to resemble long-term infrastructure contracting. South Korean manufacturer SK On signed an agreement totaling 20 GWh of batteries with U.S. startup Slate, covering deliveries from the mid-2020s into the early 2030s. Slate is building a modular EV truck platform for cost-sensitive fleets and small commercial operators, based on a simplified, highly configurable electric chassis rather than traditional big-box OEM channels. With a locked-in cell pipeline and a standardized chassis that upfitters can customize, the company aims to push electric work trucks into the same everyday tasks—and eventually the same mainstream procurement processes—that diesel vehicles already serve.

In emerging markets, Tunisian startup Bako Motors offered a bundled view of mobility and energy from the outset. The team designs solar-paired delivery and utility vehicles for African and Gulf cities, where grid reliability is uneven and fuel imports are expensive and volatile. Vehicles are sized for local road conditions and tuned for last-mile logistics, while distributed PV installations supply a meaningful share of their energy. This approach aligns transport demand with local generation instead of relying entirely on centralized refineries and long fuel supply chains.

Taken together, these examples portray EVs as nodes inside energy systems.

Platforms coordinate data, V2H kits turn cars into emergency assets, long-term cell contracts stabilize industrial planning, and solar-paired vehicles support local resilience and energy sovereignty.

1.3 Maritime systems and ports: fuels, compliance, and autonomy at sea

On the fuel side, a cluster of companies progressed toward shipping-grade molecules that fit existing engines and bunkering infrastructure.

British firm HiiROC agreed to supply hydrogen for a 150,000-ton-per-year clean methanol plant located next to an energy-from-waste facility in Scotland. The company uses “turquoise” hydrogen produced via thermal plasma pyrolysis of natural gas, with solid carbon as a by-product. This pathway aims to deliver lower-cost hydrogen for methanol production while limiting CO2 emissions.

In Finland, Hycamite advances a related methane-splitting process that yields low-carbon hydrogen and high-quality solid carbon by thermo-catalytically decomposing methane without releasing CO2. This positioning aligns the company with industrial decarbonization agendas and with customers that need both fuel and carbon by-products.

Downstream, shipyards and operators increasingly integrated multiple low-carbon options into actual orders. Ammonia-fueled and ammonia-ready ships moved into orderbooks, and engineering teams explored ways to adapt existing diesel-centric designs to new fuel blends. Samsung Heavy Industries deepened its collaboration with Amogy on ammonia-to-power systems, signing a multi-year manufacturing contract and expanding its ammonia demonstration facility at the Geoje Shipyard.

These facilities test and industrialize Amogy’s modules for future vessels and turn ammonia power systems into a tangible part of the shipbuilding toolkit.

This stack—methane- or ammonia-based fuels at the production end, flexible onboard power systems on vessels, and project-finance structures in the middle—creates a framework where long-life fleets can move under tightening climate and emissions rules.

Alongside fuels, maritime autonomy and risk analytics matured. Newlab’s New Orleans hub is being built at the former Naval Support Activity site as an industrial development facility focused on energy, carbon, shipping, and maritime innovation.

The space gives startups a place to assemble and pre-commission first-of-a-kind units in port-adjacent conditions, with real infrastructure and stakeholders on site.

In parallel, Pole Star expanded vessel-tracking and sanctions-screening platforms that combine ship telemetry and ownership data with global watchlists. Banks, insurers, and operators use these tools to monitor compliance and route risk in real time. In practice, services like these now sit close to the core of maritime risk infrastructure, shaping what routes, charters, and financings remain viable.

For ports, shipowners, and capital providers, the sea in 2025 looked like a convergence of molecules, machines, and monitoring systems. Fuel pathways, onboard power modules, and compliance dashboards all influence which ships get financed and which routes remain attractive.

1.4 Aviation’s split screen: SAF, e-fuels, and new regional architectures

Aviation operated on two linked tracks.

On one track, sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) and e-fuels carried most of the near-term decarbonization load. On the other, new aircraft architectures—hydrogen-electric, blended-wing bodies, and eVTOL—competed for specific niches where they could fit regulatory and operational constraints.

On the fuel side, the EU’s ReFuelEU Aviation package set a binding mandate that starts at 2% SAF in 2025 and rises to 6% in 2030, 20% in 2035, and up to 70% by 2050. This timeline effectively creates the world’s largest green-fuel mandate for aviation. Current European production sits well below the levels required for a net-zero trajectory, and recent SAF industrial policy analysis and EASA status reports highlight the execution gap in volume, feedstocks, and financing.

Swiss startup Metafuels positioned itself directly in this policy-driven space. Its aerobrew process converts sustainable methanol, including e-methanol, into e-SAF via a catalytic route designed for higher energetic efficiency and very high carbon conversion compared with conventional power-to-liquid pathways.

Current operations sit at pilot scale, on the order of liters per day in the lab, with projects such as the Pizol and Turbe plants targeting around 12,000 liters per day by the second half of the decade. The company has raised capital on the premise that a more efficient e-SAF pathway can make mandated volumes bankable for large plants rather than purely regulatory.

On the aircraft side, regional and short-haul missions served as the main proving ground for new architectures. In the UK, RVL Group partnered with ZeroAvia to launch hydrogen-electric cargo services using the ZA600 powertrain on converted Cessna Caravan aircraft, subject to UK Civil Aviation Authority approvals.

Target routes sit in the few-hundred-mile range and address cargo first, where noise and emissions benefits align with relatively modest range requirements.

The regulatory backdrop also advanced. EASA’s 2025 revision of the Standardised European Rules of the Airclarified how crewed VTOL aircraft operate in European airspace. This step gave advanced air mobility operators a concrete framework instead of a purely conceptual status.

In parallel, regional experiments continued across eVTOL manufacturers and blended-wing projects. JetZero is developing a composite blended-wing-body demonstrator under a $235 million U.S. Air Force contract. The demonstrator explores both aerodynamic gains and new cabin and cargo layouts.

Autonomy in the air continued to industrialize through programs like Reliable Robotics’ work on the Caravan. These efforts focus on cargo and logistics aircraft that can operate with higher tempo and lower crew risk once certification paths mature, instead of focusing solely on futuristic air-taxi concepts.

Overall, the sector follows a clear sequence. SAF and e-SAF carry most of the decarbonization lift in the current decade. Hydrogen-electric systems, BWB, and VTOL platforms compete for niches where their performance, infrastructure demands, and regulatory profiles can justify dedicated investment.

2. Agri & Food Tech

In agrifood and food tech, 2025 showed that deep tech in food now covers much more than new products on the shelf.

It also covers how protein, land, and buildings enter climate planning, resilience strategies, and financial models.

Fermentation-enabled alternative proteins, tracked in mid-year overviews of alt-protein and cellular agriculture developments, now sit alongside market analyses such as this summary of funding and consolidation trends.

Vertical farms were assessed as energy-intensive buildings with specific cost structures, with the market shake-out documented in reports on controlled-environment players exiting the market. Soil and carbon programmes, including Indigo Ag’s soil-carbon credits delivered to Microsoft, linked agronomy directly to corporate climate commitments.

So, for builders and backers, agrifood increasingly resembled a capital-intensive infrastructure loop where biology, hardware, and regulation meet, rather than a classic consumer-brand category.

2.1 Protein shifts from novelty to infrastructure

Across seeds, fermentation, fungi, and molecular farming, protein moved deeper into the infrastructure conversation.

On the crop side, Inari advanced its trait-engineering and computational breeding platform with a new funding round. The company’s funding announcement and analyses of climate-resilient, high-yield seeds present this work as a response to fertiliser constraints, yield variability, and food-security concerns. In this context, the platform positions seeds as a financing tool for climate and food systems, by making yields and input requirements more predictable for downstream investors and operators.

In fermentation, Finnish firm Solar Foods progressed toward larger-scale production of its gas-fermentation protein Solein. Company materials on technology and roadmap and external analyses of conversion efficiency and land-use impact describe a system in which “protein from air and electricity” operates as a grid-plus-fermentation asset. In this setup, electricity, gas-handling equipment, and fermenters form a single infrastructure block that can be located near renewable generation and provide a steady stream of protein ingredients.

Building on this, single-cell protein (SCP) platforms further along the fermentation stack increasingly target agricultural and industrial side streams. The concept is to collect waste and residues and convert them into feed and food ingredients through high-productivity fermentation.

Overviews of fermentation as a platform for alternative protein and investment outlooks on molecular farming and related approaches emphasise a central point: over the long term, bottlenecks tend to form around fermentation capacity and low-cost inputs, while consumer demand and branding develop on top of this production base.

Within this wider fermentation context, German startup Kynda raised about €3 million in seed funding to scale its mycoprotein ingredient platform. Its biomass-fermentation ingredients are positioned as B2B inputs for food, feed, and bioproducts.

The ingredients are designed as drop-in materials that fit into existing manufacturing pipelines and supply contracts, so the commercial logic aligns with other bulk ingredients and intermediates.

In parallel, Finally Foods advanced a different route through molecular farming. The company announced field trials for potatoes engineered to produce casein, the principal dairy protein. An update outlines the use of AI-enabled trait design to bring dairy-grade proteins into field crops. If agronomy, logistics, and extraction economics scale as planned, part of dairy-protein production can move from stainless-steel bioreactors into staple agriculture that uses familiar farm and storage practices.

Taken together, these developments also drew attention to areas where protein infrastructure is under pressure, especially for single-product, capex-heavy facilities.

2.2 Carbon, compliance, and land as a climate asset

Agrifood also sat at the centre of how land was treated as a climate and compliance asset, especially through carbon removal and soil-carbon infrastructure.